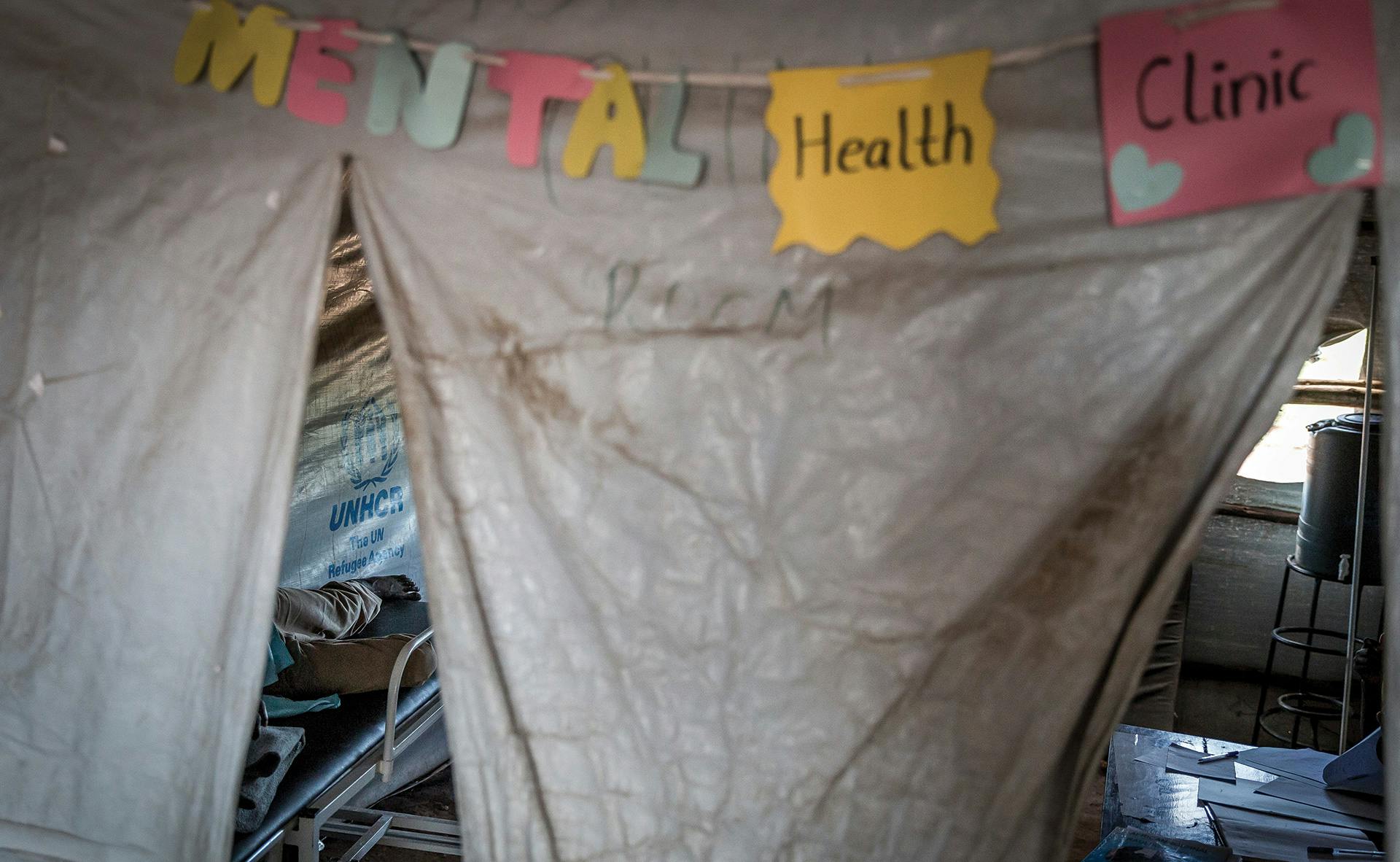

The mental health of refugees, as opposed to their physical well-being, is not always recognized as a top priority during humanitarian responses. Refugees may experience terrible trauma before, during, and after fleeing their homes, all of which can contribute to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), among other mental health disturbances. Even assuming refugees are given a new home in a host country after their displacement, further struggles can cause yet more mental stress. Treating this may not be as obvious as providing for basic needs, but it's also important.

Refugees suffering from PTSD may have experienced traumas beyond forced relocation and loss of livelihood, including enslavement, starvation, torture, rape, and other acts of violence. Even when the trauma itself is over, PTSD can render affected persons depressed, inconsolable, and at times completely unable to function.

According to the American Psychiatric Association (APA), “People with PTSD have intense, disturbing thoughts and feelings related to their experience that last long after the traumatic event has ended. They may relive the event through flashbacks or nightmares; they may feel sadness, fear or anger; and they may feel detached or estranged from other people. People with PTSD may avoid situations or people that remind them of the traumatic event, and they may have strong negative reactions to something as ordinary as a loud noise or an accidental touch.”

In the case of refugees from the Syrian civil war, millions of people were displaced from their homes, hundreds of thousands were killed, and the standard of living in their native country was set back decades; it’s difficult to know where to begin the mental health conversation. “Children under the age of eighteen represent about half of the Syrian refugee population, with approximately forty percent under the age of twelve," according to a 2015 report from the Migration Policy Institute. "Syrian refugee children are also at risk for a range of mental health issues, having experienced very high levels of trauma: 79 percent had experienced a death in the family; 60 percent had seen someone get kicked, shot at, or physically hurt; and 30 percent had themselves been kicked, shot at, or physically hurt. Almost half displayed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—ten times the prevalence among children around the world.”

In many cases, even the logistical stress of relocation can lead to reliving past traumas. For example, although Latin Americans attempting to cross from Mexico into the United States likely experience less violence than Syrian refugees, they still endure similar mental stress. Dr. Gaurav Mishra, a child and adolescent psychiatrist in southeastern California's Imperial County, wrote in a presentation that “migration around the border is related to stressors that could lead to higher incidence of anxiety disorders among Hispanic youth compared to other ethnic groups.” Mishra cites the case of a 13-year-old girl whose PTSD, combined with thoughts of self-harm and depression, were treated successfully with a combination of medication and relocation (she was moved to a new school due to bullying).

Potentially even more troubling, living in the anti-immigrant political climate in the U.S. -- the feeling of being unwanted and targeted -- can trigger suicidal thoughts in a refugee already struggling with PTSD. The Refugee Health Technical Awareness Center (RHTAC) identifies several "risk factors" for those who may attempt suicide, including "feelings of hopelessness" and "social isolation." Mental health issues often still carry a stigma, so that many refugees may feel uncomfortable seeking help. Others may not even know that help is a possibility, or even realize they need help.

It's critical to increase awareness of mental health issues faced by refugees, and it's especially important that service providers know the warning signs. RHTAC, an organization funded by the United States Department of Health & Human Services' Office of Refugee Resettlement, is dedicated to improving the lives of refugees by looking at their unique health needs. Part of their efforts include online tools and webinars to help health care workers, social services personnel, and others better understand and relate to the refugee experience and to communicate and engage with those they're attempting to assist.

Economic chaos in Venezuela has set off what the New York Times called a “staggering exodus” of refugees —among the largest in Latin American history. Most of those fleeing are malnourished and have been for some time; the insufficiency and lack of health care, food, water, and information has driven hundreds of thousands of displaced peoples to surrounding Latin American countries as well as the United States. Based on research gathered by the social psychologist Yorelis Acosta, “A predominance of negative emotions such as sadness, fear, and anger” are currently the norm in Venezuela. While Acosta and his peers in Venezuela are doing what they can (including setting up a hotline for those in distress), it's an open question what, if anything, can be done at this point to stabilize mental health for those who have already fled.

In fact, it's hard to know what can be done for refugees suffering from PTSD in general, wherever they are. When it comes to diagnosing the disorder, the APA describes symptoms as falling into four categories: “intrusive thoughts,” “avoiding reminders,” “negative thoughts and feelings,” and “arousal and reactive symptoms.” As for treatment, cognitive behavior therapy is a popular course of action in typical circumstances, along with other forms of psychotherapy coupled with psychotropic medications, such as SSRI antidepressants.

However, “there are many challenges in the detection and effective treatment of mental health problems in refugees," cautions RHTAC in its mental health primer. "Often language and cultural barriers and biases, whether of the refugee or the provider, can hinder identification of problems and the development of a therapeutic relationship. Furthermore, there is little evidence for the efficacy of any particular treatment strategy. Much work remains to be done to develop culturally competent means of screening refugees for mental health issues, and then implementing evidence-based interventions, both at an individual and community level, for these common and frequently debilitating diagnoses.”

PTSD and acute stress disorder (an anxiety disorder that causes symptoms similar to PTSDs) are especially difficult issues to overcome for refugee children trying to adjust to new homes, communities, and schools. Getting used to a new school can be particularly stressful. According to the RHTAC, “Children may need to integrate into school settings that are unfamiliar and sometimes academically beyond their educational background. Children must learn a new language and culture, and frequently must navigate between a markedly different home and host-country culture." And this doesn't even begin to touch on the possibility of differences in ethnicity, religion, race, or nationality, which can make the child a target for bullying, harassment, isolation, or other forms of abuse.

As for adult refugees, learning a new language, adapting to a foreign culture, finding employment and shelter, and caring for one’s family amid often unfriendly conditions are all very stressful, and can cause someone prone to or suffering with PTSD to regress into the past and relive past trauma. Grief over separated or deceased family members is also an all-too-common stressor.

RHTAC's offers a candid assessment of the crisis in refugee mental health: “While the screening for and treatment of infectious diseases has been studied and practiced for decades," the organization declares, "the identification and treatment of mental health problems has lagged far behind due to complex and varied cultural contexts and languages, scattered refugee populations, and the relative lack of evidence-based interventions.” Given the larger and welcome trend of working to find new ways to help refugees begin a stable, sustainable life rather than simply treating their basic needs, addressing their mental health should also become an urgent priority rather than an afterthought.