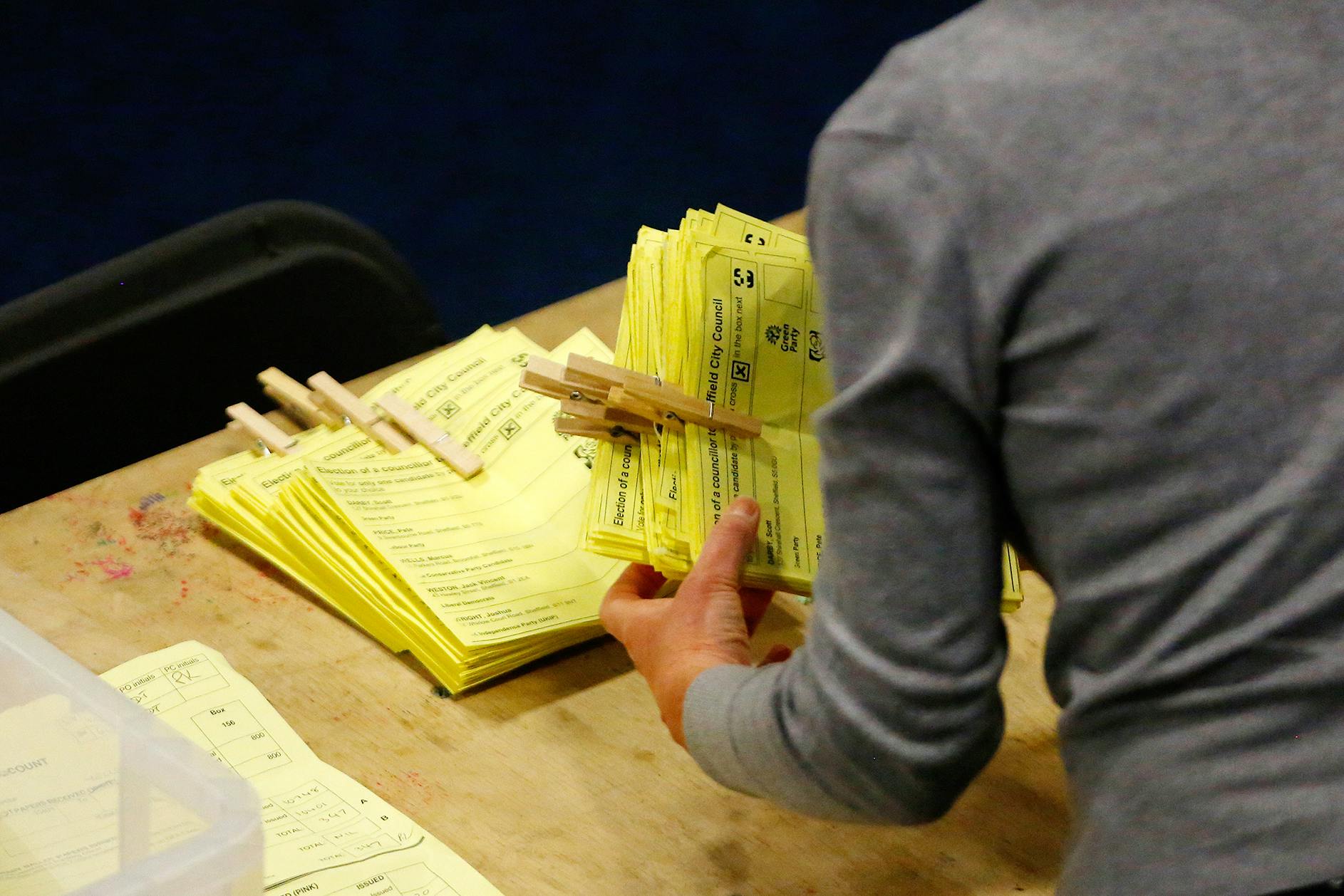

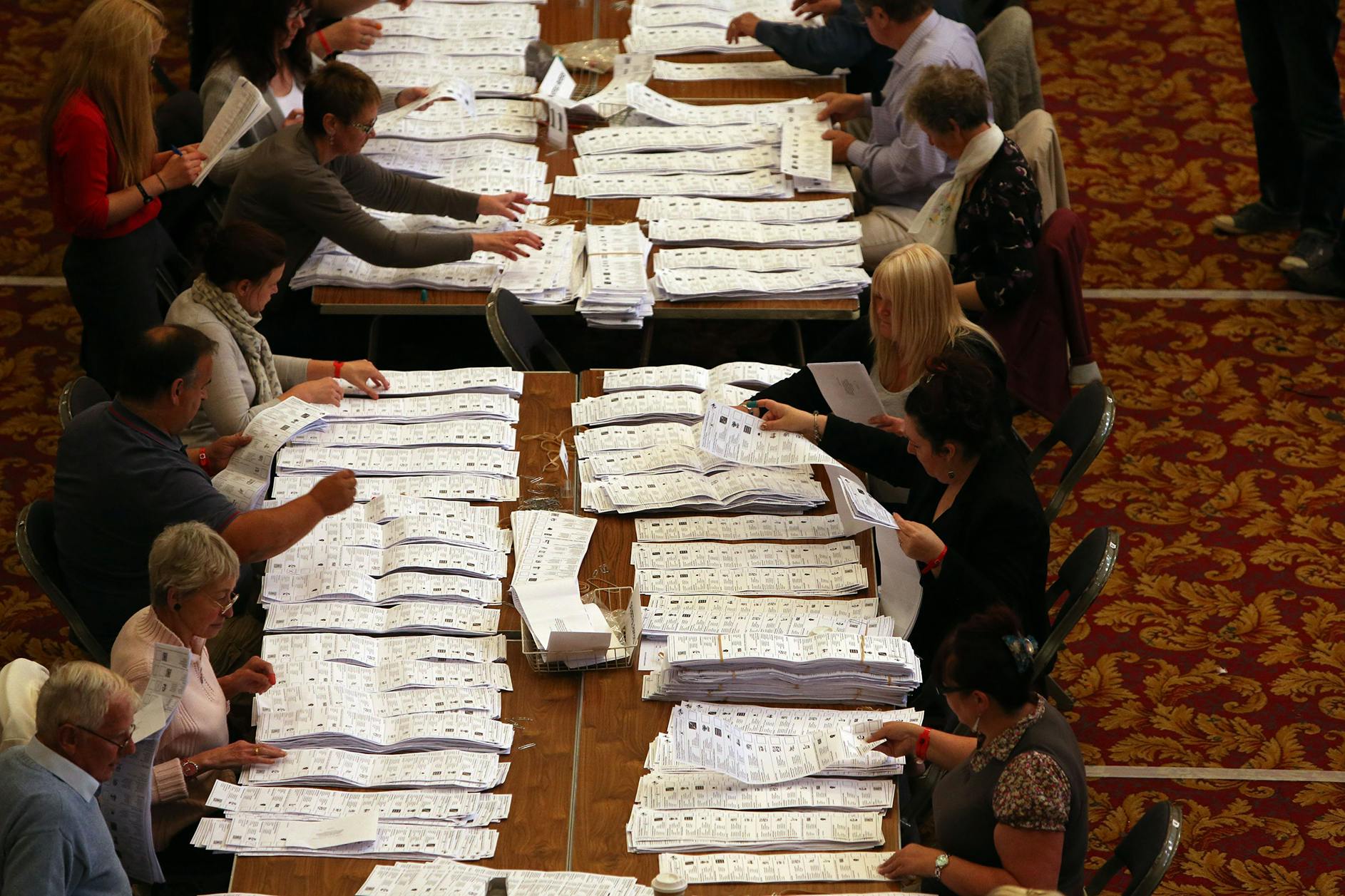

While technology lets us tweet globally and order a pizza locally within seconds of each other, the tech that powers elections in many parts of the world runs at an altogether slower pace. The months of meticulous preparation might begin with careful forecasting and painstakingly precise orders of ballot papers, boxes, and pencils. In the United Kingdom, one of the oldest companies providing election supplies to councils up and down the country has been operating since 1750.

The United Kingdom’s officers may still argue with their suppliers over the thickness of the ballot papers, the size of the ballot boxes, and the number and type of pencils required for plebiscites. And the nation currently has no plans to drag its democracy into the modern day: a parliamentary committee was opened to explore electronic voting in 2014, but hasn’t released any findings in the intervening four years. But most countries are bringing their elections into the 21st century by adopting technological solutions.

“How beneficial that is depends on the system you’re in,” says Nic Cheeseman, professor of democracy at the University of Birmingham in the UK, and co-author (with Brian Klaas) of the book How to Rig an Election.

Most countries with the greatest need for technological solutions won’t be able to take best advantage of the benefits they provide. “There’s a bit of a Catch-22,” says Cheeseman. “Where you need, really need, this technology, it’s least effective. You need this tech in countries where you can’t trust the electoral commission or the ruling party, and that’s where it’s most likely to break down because it’s the most vulnerable.”

For example, newer tech is being rapidly rolled out for elections across Africa, where in some cases, despots and dictators try to maintain a stranglehold on power. Roughly half of all elections in Africa use some kind of technology during the election process, whether for registering voters, verifying counts, or transmitting results. Such technology, conventional wisdom goes, will help nullify any voting malfeasance instigated by the ruling party. But that assumption is far from correct.

“There’s a naivety that just because you gave a process a technological name like ‘biometric voter registration’ or ‘e-voting’ meant it was better than doing it the old-fashioned way,” says Michael Yard of the International Foundation for Electoral Systems, an advisory body that has helped run elections in 145 different countries. Yard has been an adviser or IT director for elections in more than 50 different countries worldwide over his 24-year career. “It’s a naive perception that technology will make things better—and sometimes magically—without even bothering to understand what it means.”

In addition to also providing what’s sometimes a false sense of security, technology is also more expensive. In European elections, the cost of holding an election—from start to finish, registering the voters then tallying the ballots they cast—costs around $1 per voter. The amount can vary depending on any number of factors, but that’s the level at which election costs are typically estimated. In Africa, that number increases to something between $15 and $20 per voter. “African elections have become some of the most expensive in the world,” says Cheeseman, in large part thanks to the introduction of digital technology.

“If you had a choice between two technologies that were the same cost, then go for the digital technology every time,” he says. “But the problem is that’s not what you’re faced with.” Tech-powered elections can cost anywhere between $30 million and $100 million more to stage. “Digital technology just doesn’t seem right now to be performing in any worthwhile way, given the cost.”

Digital voting systems are not cheap and—in the wrong hands—can be easy to manipulate. Cheeseman has a solution. “Instead of spending $30 million on a wonderful new digital technology, you could spend $5 million on building a really good system of opposition party agents,” he says. “It would cost you one-sixth of the cost of the tech, but be just as effective.”

Yard also sees that as a solution. “I’d advocate giving political stakeholders a certain number of tickets,” he says. “You can hand-select 10 polling stations you think might have the greatest suspicion of fraud, and we’ll do a manual count of those 10.”

The problem with that is convincing the often authoritarian ruling parties to empower any sort of opposition. “It’ll seem biased, that you’re trying to affect regime change,” says Cheeseman. Not only are incumbent political powers likely to stymie such attempts, but they’ll also place pressure on the donors who fund elections in developing countries not to bankroll the plebiscite. “What would be most efficient might be one of the things that’s most politically difficult to do,” he explains.

So instead, many countries rely on technology. “There’s a sweet spot when it makes sense to invest in tech,” says Cheeseman. That’s not necessarily when the country is a democracy, like the UK or the United States, “When you’re a democracy and can trust the democracy, you don’t need it,” he says.

Similarly, there's no point in anyone attempting to provide a veneer of respectability to elections in authoritarian states. “As we’ve moved along the technology spectrum in elections,” says Yard, “it’s become increasingly possible for one person or a small group of individuals to have a much greater impact.”

“There’s a sweet spot when it makes sense to invest in tech.”

Power outages or system failures just so happen to take place when insurgent opposition parties begin to build momentum during electronic counts; when the system comes back up, suddenly the trend that had been seen in the moments before the outage has been reversed, and the ruling party is suddenly back in the ascendancy. “The official explanation for this is server error, the network went down, or one of many possible things that it’s impossible to prove or disprove,” explains Cheeseman. “There are lots of cases now where you can see the technology will suspiciously go down for an hour and when it comes back the ruling party will have done better than it was doing before.”

That’s putting aside the risk that malicious third parties—hackers from countries seeking to derail or defraud elections elsewhere—present to the democratic process. Russia is alleged to have interfered in the democratic elections of 27 separate countries since 2004, sometimes via direct cyberattacks against e-voting systems. Then there’s the integrity of e-voting machines. Even though suppliers claim their technology is unbreakable, hackers still manage to find a way through. J. Alex Halderman, a University of Michigan computer science professor, has broken into successive generations of U.S. voting technology. He’s turned an e-voting machine into Pac-Man cabinets and recoded them to play the University of Michigan fight song.

And while the pace of technology developments continues rapidly, the skill sets of those tasked with monitoring elections to make sure they’re carried out fairly languishes behind. “International election observers typically are not technical people,” says Cheeseman. “They often don’t understand enough to arbitrate between two different accusations—that any downtime is an administrative glitch and that the ruling party deliberately sabotaged the technology.” Few international election observers include IT specialists.

In order to allow digital elections to take place more often, and to have more confidence in the validity of their outcomes, more work needs to be done by the auditors to understand the technology underlying them. “Otherwise, you’re monitoring an election in an analog way when it’s a digital election.”

Making better use of international election observers is also more important in the future as votes become more reliant on technology than traditional techniques. Kenya has around 43,000 polling stations dotted around its 225,000 square miles (583,000 square km) of territory. The European Union sends a team of 120 election observers to most countries, paired up into 60 teams of two, each of which will sit at a polling station and make sure what they see isn’t fraudulent. So in Kenya’s case that coverage is minuscule: 60 stations out of 43,000, or 0.1 percent of all the places

Kenyans can cast a ballot. “You have a serious question about whether that makes sense,” says Cheeseman. Instead, he wants to see more election monitors trained to be tech literate, and those people to be deployed where the election is organized—tackling any potential corruption at the source—while domestic observers watch the vast number of polling stations at far-flung corners of the country.

For all these reasons, it’s important to have an audit trail—something that a lot of technological solutions to elections don’t have. “As we move to technology, we shouldn’t abandon that auditability,” says Yard.

When ballots use “paper and pen you can reopen the ballot box and do a recount,” says Cheeseman. Around half of electronic voting machines in use worldwide have no way of getting the information on them off them onto paper, so you can’t audit them by hand. “That’s pretty serious in a situation where those machines are vulnerable to being hacked,” he says.

“The problem with technology is that it often creates this veneer of professionalism and competence that belies the things that can be done within that,” Cheeseman says. “Sometimes the technology removes paper trails that are one of the ways you can tell whether or not the election was good quality.”

There are no guarantees with either the old school pencil-and-paper method of voting or the newfangled, interconnected method of tech voting that elections will be free of mistakes, whether accidental or more malign. In the 2015 UK general election, some candidates, including some from the country’s second-largest political party, were left off several hundred ballot papers, while 200,000 more ballots disappeared after a van containing them was stolen in the week before the vote.

And that’s just the accidental errors. “There have always been people trying to impact the outcome of elections,” explains Yard, from ballot box stuffing to deliberate miscounting of papers. One study of nearly 1,000 elections between 1946–2000 found widespread meddling by third parties on a nation-state level, with the meddling increasing the popular-vote share of the favored party by an average of 3 percent.

“We’re seeing elections as a place to experiment with new technologies rather than election management bodies discovering a need and finding the best technologies to meet those requirements,” says Yard. “It’s technology in search of a market, rather than a problem in search of a technological solution.” And that can be problematic.

Using democratic elections as beta testing for technology that might not actually be necessary is alarming—and Yard remains unconvinced about the need for more election tech in many areas. Is there a good example of the useful deployment of technology in elections in the more than 50 countries he’s helped advise? “No,” he replies. There’s a long, uncomfortable pause. “I’ve been watching closely in terms of the introduction of technology, and don’t see it,” he says. “Maybe someone is doing it and I’ve not seen it, but no, I haven’t seen a good use.”

Traditional pen-and-paper election methods may be entering their old age, struggling to survive against the nimbler, younger, more attractive alternative of technologically enhanced votes. But they’re not dead yet.