THIS SUMMER, IN THE SOUTH AFRICAN capital of Johannesburg, former United States president Barack Obama delivered a lecture that was a rallying cry for democracy. Obama was invited to speak to 15,000 South Africans gathered in a sports stadium to mark the centennial of Nelson Mandela’s birth.

“It is tempting to give in to cynicism: to believe that recent shifts in global politics are too powerful to push back; that the pendulum has swung permanently,” said Obama. “Just as people spoke about the triumph of democracy in the nineties, now you are hearing people talk about end of democracy and the triumph of tribalism and the strongman. We have to resist that cynicism.”

It is easy to be cynical when witnessing what is happening in even some of the world’s most liberal democracies. When a far-right political party made gains in the Swedish election in September 2018, it was at once both surprising and somehow inevitable. Surprising because Sweden is often considered to be a model of modern, liberal democracy: it recently came third in a list of the most liberal countries in the world, behind its neighbors Iceland and Finland. (The ranking was based on data from Yale University, the World Economic Forum, and the Social Progress Index.)

However, when it’s considered in the wider context of recent electoral trends, the rise of the Sweden Democrats, who won 17.6 percent of votes, can be seen as part of a wider political trend across Europe. The result follows electoral gains for nationalist parties in Germany and Italy. In addition, the far-right Freedom Party is now the second largest political party in the Netherlands, and nationalist candidate Marine Le Pen challenged Emmanuel Macron in the 2017 French presidential election.

The rise of nationalism and populism in seemingly moderate democracies is a worrying trend that is in part a response to the European refugee crisis. It is a disturbing turn of events for those who support open, liberal democracies, but it is one that should be kept in perspective. While these parties are clearly finding support for their anti-immigration rhetoric, they remain on the fringes of power.

The real threat to democracy from nationalist and populist political parties is when they come to power. Over time, these parties gradually form governments that have a tendency toward the erosion of civil liberties, a free press, and other democratic values, according to Annika Silva-Leander. She is head of Democracy Assessment & Political Analysis at the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA), an intergovernmental organization based in Stockholm, Sweden.

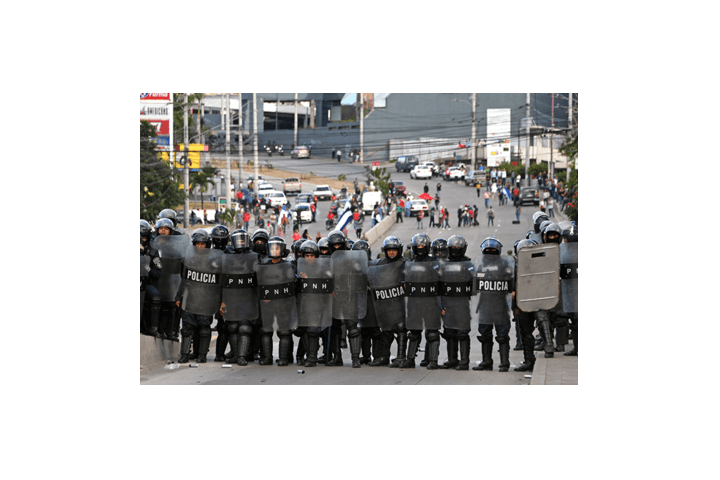

Silva-Leander points to a form of modern “democratic backsliding,” in which freedoms are eroded over a much longer period of time than in the military coups that typified previous generations. “It’s not traditional backsliding, with a military coup and rapid declines in freedoms within one year,” she says. “Instead, it’s gradual. In Venezuela, for example, it’s [happened] over the past twenty years since Hugo Chavez was elected, and has continued under successive governments. In Hungary, it has happened over the past ten years, and in Poland it is more recent.”

“The rise of nationalism and populism in seemingly moderate democracies is a worrying trend.”

Despite these governments’ retaining the semblance of democracy through free and fair elections, explains Silva-Leander, they preside over a decline in other kinds of democratic values. “In Poland and Hungary we see a decline in civil liberties, restrictions on media freedoms, and restrictions on civil society. These reforms that are undermining and hollowing out democracy are being carried out by democratically elected politicians. They use democratic instruments to undermine democracy from within. That is what is quite scary to see and quite a new phenomenon compared to the military coups of Latin American regimes in the 1970s, for example.”

Such “democratic backsliding” is apparently occurring in both established and less-established democracies across the globe. When the U.S.-based nongovernmental organization Freedom House published its annual Freedom in the World report for 2018, it subtitled it “Democracy in Crisis.” The report listed 71 countries that suffered net declines in political rights and civil liberties in 2017, with only 35 registering gains. This marked the 12th consecutive year of decline in global freedom as measured by the report, which was first published in 1972.

“DEMOCRACY IS IN CRISIS,” WROTE FREEDOM House president Michael J. Abramowitz in the report. “The values it embodies—particularly the right to choose leaders in free and fair elections, freedom of the press, and the rule of law—are under assault and in retreat globally. States that a decade ago seemed like promising success stories—Turkey and Hungary, for example—are sliding into authoritarian rule. The military in Myanmar, which began a limited democratic opening in 2010, executed a shocking campaign of ethnic cleansing in 2017 and rebuffed international criticism of its actions.”

“Meanwhile,” he continued, “the world’s most powerful democracies are mired in seemingly intractable problems at home, including social and economic disparities, partisan fragmentation, terrorist attacks and an influx of refugees that has strained alliances and increased fears of the ‘other.’”

“A free press is essential to a functioning democracy.”

Freedom House’s 2018 report takes particular aim at the state of democracy in its home nation, the U.S. It claims that “the past year brought further, faster erosion of America’s own democratic standards than at any other time in memory.” It strongly criticizes President Donald Trump’s public attacks on the media, judiciary, and law enforcement agencies as an assault on democratic institutions.

WHILE U.S. DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTIONS HAVE remained resilient to these attacks, the report warns that “the administration’s statements and actions could ultimately leave them weakened, with serious consequences for the health of US democracy and America’s role in the world.”

Back in Johannesburg, Obama used his lecture to remind the world of the importance of democratic institutions and, in Mandela’s words, that “democracy is about more than just elections.”

Obama also pointed to the worrying rise of the so-called political strongman. “Strongman politics are ascendant suddenly, whereby elections and some pretense of democracy are maintained—the form of it—but those in power seek to undermine every institution or norm that gives democracy meaning,” said Obama. “In the West, you’ve got far-right parties that oftentimes are based not just on platforms of protectionism and closed borders, but also on barely hidden racial nationalism. Many developing countries now are looking at China’s model of authoritarian control combined with mercantilist capitalism as preferable to the messiness of democracy.”

Under Western analysis, examples of such strongmen typically include populist leaders like Russian president Vladimir Putin, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, and Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte.

Putin’s promise of strength and putting Russia first enjoys huge support from voters, as does Duterte’s violent two-year war on drugs, which has reportedly claimed 4,500 lives, according to his own government’s statistics (others believe the real total could be as high as 20,000 lives).

BUT A CURSORY LOOK AT HOW SUCH LEADERS have handled just one of the democratic institutions, freedom of the press, shows the negative impact they have on democracy. “A free press is essential to a functioning democracy,” says Media Legal Defence Initiative CEO Lucy Freeman. “In Russia and Hungary, critical news outlets have been shut down or bought out, media owners have been hit with spurious allegations—tax evasion or failure to obtain licenses—and journalists have faced criminal charges. Attempts to restrict publishing online have also been vigorously pursued.”

In the Philippines, meanwhile, journalists who have attempted to criticize Duterte’s violent campaign have found themselves or their families receiving threats of violence, according to Freeman.

However, to believe that democracy is failing across the globe is to believe the strongman’s lie. It suits such leaders that the electorate believe democracy is failing. But that is far from the truth.

Despite some recent setbacks, the longer-term overall trend has been toward democracy rather than away from it. There are now nearly three times the number of electoral democracies in the world than there were 40 years ago, according to International IDEA’s 2017 report The Global State of Democracy. That is an increase from as few as 46 countries in 1975 to 132 countries in 2016.

The report tracks five key areas, or “indices,” between 1975 and 2015. Four of them—Representative Government, Fundamental Rights, Checks on Government and Participatory Engagement—have risen over the past 40 years. Only one category, Impartial Administration, has remained f lat, which the report says shows how “corruption and predictable enforcement are as big a problem today as they were in 1975.”

International IDEA plans to release an updated report for 2019. Joseph Noonan, an associate program officer in the organization’s Democracy Assessment and Political Analysis Unit, says that the latest research ref lects the findings of other organizations such as Freedom House: namely, that between 2015 and 2018 there have been more countries experiencing declines in democracy than those experiencing rises.

“The longer-term overall trend has been toward democracy rather than away from it.”

However, the countries suffering a decline in democracy are still a minority. Most democracies on the planet are neither improving or backsliding, and there are more of them than ever before. While 20–30 countries are experiencing change within their democratic processes, about 125–130 countries have maintained the same democratic level.

“We still don’t see any declines in global averages, but what we are seeing is more countries experiencing declines than experiencing increases,” says Noonan.

THERE ARE ALSO, OF COURSE, COUNTRIES where democracy is making steady progress. Countries such as the Gambia, which after 22 years of authoritarian rule had free elections in 2016. And Tunisia, the only country to emerge from the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings as a democracy.

Obama reminded the Johannesburg crowd that “democracy can be messy, and it can be slow, and it can be frustrating,” but that “the efficiency that’s offered by an autocrat, that’s a false promise. For all its imperfections, real democracy best upholds the idea that government exists to serve the individual and not the other way around.”

Recent setbacks for some of the world’s most established democracies are cause for concern. But they are not reasons to conclude that democracy is not working, or not gaining ground overall. Democracy today is being shaped by geopolitical issues such as immigration and climate change. But, like every other area of modern life, it is also being radically affected by digital technology.

Some of the most high-profile examples of technology being used in the democratic process are negative ones—Russia’s alleged interference with the U.S. 2016 presidential elections being the most prominent. Similar uses of technology used for political interference, particularly the spreading of misinformation, are alleged to have occurred in other votes, including the UK’s referendum on continuing its membership in the European Union.

WHILE THERE IS CLEARLY A DARK SIDE TO digital technology’s involvement in democracy, Silva- Leander sees plenty of positive examples of the role technology can play: “Digital technology has opened up new spaces for citizens to engage in the political area. It has decreased the cost of advocacy campaigns. It has provided new mobilization opportunities. Through social media you no longer have to go out on the street to demonstrate and protest. You can directly present your demands on social media, through online polls and other instruments. It facilitates participation and citizen engagement in many ways. It also reduces the distance between decision-makers and politicians and the people.”