I FIRST MET PAUL-EMMANUEL LEVY IN PARIS in October 2017, at the first global summit to be held by Techfugees, a nonprofit that helps coordinate the international tech community’s response to the needs of refugees. Earlier that day he had been fervently pitching his start-up Quickbed, which optimizes accommodation availability for the homeless. Levy told me he’d given up his job in investment banking to develop Quickbed, and he wasn’t sure how much longer he and his chief technology officer could continue without any funding.

The next time we spoke was in May 2018. After “two good years” developing two versions of the platform, his CTO had left to focus on his family. Levy now needs to raise €15,000 so he can engage an agency to program the next version. Then Quickbed can be officially piloted.

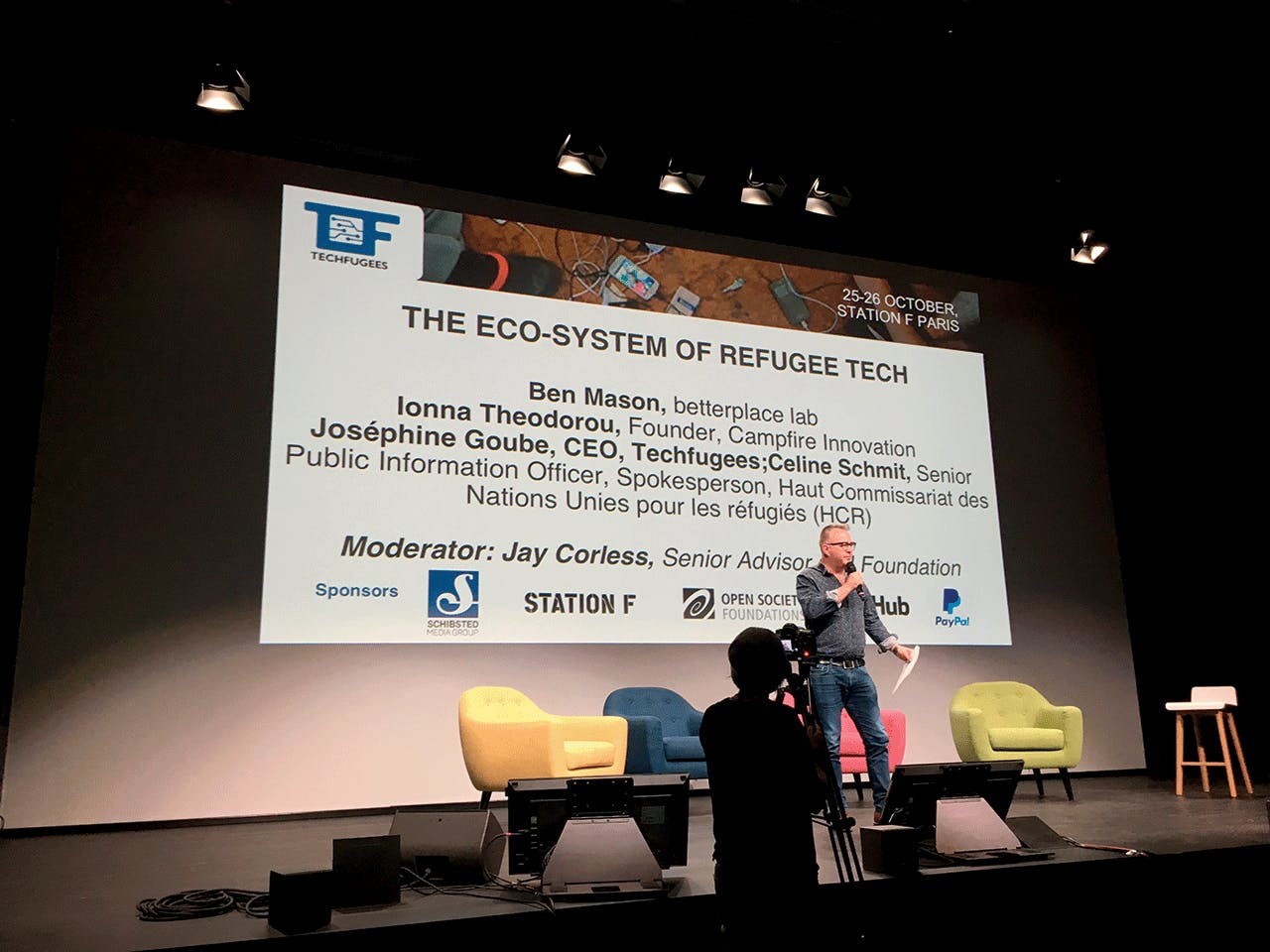

Techfugees was founded by Mike Butcher, editor-at-large of the technology news website TechCrunch, during the peak of the refugee crisis in 2015. He believed that the technology world’s “considerable firepower” could help provide digital solutions for refugees as well as NGOs and other groups. Butcher then brought London-based Joséphine Goube (named one of Forbes’ 30 Under 30 social entrepreneurs in 2016) onboard as COO, then eventually as CEO. Chapters now exist in around 25 countries, including the United Kingdom, France, Kenya, Australia, Italy, Turkey, Lebanon, and the United States.

“Techfugees is a global community of 18,000 techies, start-ups, NGOs, impact advisers, refugees, and entrepreneurs all over the world who increasingly turn to each other for support, information, and best-practice sharing,” said Goube. “It supports the projects that emerge from local chapter events by connecting and partnering with key players, some of which help the start-ups with expertise, advice, space, resources, communication, and so on.”

Through conferences, workshops, hackathons and meetups, the Techfugees community supports tech services across five areas: infrastructure, education, identity, health, and inclusion.

Levy’s idea for Quickbed came about after discussions with his father, who runs Hébergement d’Urgence in Paris—emergency accommodation for homeless people, including asylum seekers. He discovered that a lack of communication between the associations meant they don’t always have an overview of where the free beds are. “About 2 percent of 140,000 beds are unoptimized, which is huge,” he explained.

The first homelessness census in Paris this year estimated there were 3,000 people sleeping on the streets nightly. Going forward, the Quickbed platform could be scaled up and adapted for similar uses in any country. But finding a marketable platform has been challenging.

“At first, we wanted to create an Airbnb for social accommodation, but if you go to the association, they tell you, you don’t have enough establishments,” Levy said, “and the establishments don’t need a platform to optimize their bookings.” To make it work, he decided to focus on a platform that puts efficiency of the establishment at the center of the value proposition.

The second version of Quickbed became a productivity tool for establishments, with such features as invoices, room management, social support, and housekeeping. Levy said it’s possible to spend 20–30 percent less time on administrative tasks by using Quickbed. The tool can also record data about a resident’s social integration (for example, at what point they request French lessons, or ask where local sports facilities are). “This will allow us to understand how best to manage the integration of a resident,” he said.

The €15,000 Levy needs would be enough to create a new Quickbed ready for trials. “We have establishments ready to test the platform who are hosting nearly 1,000 people every night, so it would be a significant test,” he said. “After that, we have a very long shortlist of establishments—such as homeless charity Emmaus, who are hosting four to five thousand people every night—who would love to test it. But they need some credentials [from us] first, and that’s normal.”

Levy said he’s not sure he could have continued without support from Techfugees’ ecosystem. “I think keeping pace of the network and the tech companies trying to make an impact in this sector is really essential,” he said. Levy recently joined the board of the French chapter of Techfugees, which is headed by Joanna Kirk, a managing director at StartHer and a cofounder of Startup Sesame.

Techfugees is just one locus of refugee-focused activity in the tech sector, much of which arose in response to anti-refugee sentiment elsewhere. In recent years, while humanitarians and human rights groups lobby governments to welcome refugees from a wide range of conflicts and disasters, the political landscape in the UK, the U.S., and Europe has grown increasingly hostile.

When Hungary acted against the rights of newcomers in 2015, a Hungarian living in Norway at the time, Balázs Némethi, felt compelled to do something. He researched the refugee crisis and realized that because homes were being destroyed and papers were lost, many refugees existed with no official identity. Among Syrian refugees, for example, the Norwegian Refugee Council has reported a “documentation crisis” and estimated that 70 percent of refugees lack basic identity documents.

In response, Némethi founded Taqanu, a blockchain-based digital platform that would enable refugees to prove their identity. Initially the goal was to open a financial ecosystem and create bank accounts for refugees. However, local and country-specific regulations became a sticking point, so the idea evolved.

“Even if we could find a country willing to use alternative methods of banking, it’s just one country—it would take a lot of time to cover 27 countries, and then we’re only Europe,” said Némethi. “So as our team started to grow with more technical expertise, we took a very business-driven approach to find a way to solve the issues of digital identities in every sector.”

He said that they are now building a B2B2C model and finalizing the core infrastructure piece that will offer the easiest way to implement a self-sovereign identity framework for organizations.

“We have been focusing on how we can create a model that not only empowers users to work with a sovereign identity, but also to create benefits for businesses, services, and INGOs [international NGOs] which can also be empowered by using the system,” he said. “It will give them the ability to shave money off operations.”

While the company now has a dual focus on business and the humanitarian sector, it maintains a good relationship with globally recognized INGOs. Némethi said he’s working on getting a proven track record with other projects first, including a fair-trade supply-chain solution, which is launching soon. Then he can go back to the INGOs and prove that the technology is ready to provide digital IDs to refugees.

Technology-based solutions like Taqanu can work because a high percentage of refugees are tech-savvy and carry smartphones. While many NGOs target the most vulnerable communities, Aline Sara, CEO and founder of NaTakallam (Arabic for “we speak”), said that hers reaches out to “highly skilled and talented” refugees who nevertheless find themselves with no way to earn income.

NaTakallam, which started in 2015, leverages the gig economy to connect language learners anywhere in the world with displaced people who can teach them Arabic—in particular the Levantine dialect—over Skype. More recently, NaTakallam has also partnered with the head of the Arabic department at Cornell University to offer students a fully structured, Ivy League curriculum.

Born in Lebanon and raised in New York, Sara spent several years working in Lebanon as a journalist and human rights advocate prior to getting her master’s from Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs. Struck by the number of refugees in Lebanon who found themselves in limbo and unable to work, she became dedicated to the idea of supporting them. “We can’t just keep turning our backs on the situation,” she said.

Today, the team at NaTakallam is made up of five full-time and four part-time staff and several dedicated interns. They’ve worked with over 115 displaced people so far. “We want to provide refugees with the minimum wage in their host country,” said Sara, adding that Lebanon is one of the countries where they have the most teachers and where the minimum wage is $450 per month.

“Around 80 percent of refugees who work with NaTakallam say it’s their only source of income, so we’d like to make it their livelihood,” she said. “To do that, we have to provide each teacher with a good number of students, given that the price is between $10 and $30 per session.”

One of the biggest challenges is people’s “distorted understanding of who refugees are,” according to Sara. “Sometimes when I present NaTakallam, people think the students are teaching the refugees. People have this ingrained idea of the helpless refugee, when really what we can bring them is a platform where they can leverage their skills and teach us.”

Although not an official partner, Sara said that NaTakallam is always in contact with Techfugees. “Start-ups are nimble, can move quickly and think disruptively, offering a good complement to more traditional forms of aid,” she said. “Techfugees brings all the different actors to the table—this is unique and certainly a positive way to move forward.”

One example of how Techfugees chapters work with each other is the launch of the first mentoring program for female refugees in Paris, which provides weekly networking and workshop sessions. “The aim is to help them understand the French market better, teach them some of the best tools to build their projects, and introduce them to mentors and potential employers,” said Joséphine Goube.

Educational access is a common theme in the space. Berlin’s Kiron Open Higher Education, founded by Vincent Zimmer and Markus Kressler to help refugees access a university education, is currently tackling a female empowerment campaign. Kiron’s data shows that only 17.2 percent of their 3,200 refugee students are female. Since Kiron’s vision is to make higher education accessible to all, he and the rest of the team are looking to equalize this ratio.

“Technology is no silver bullet in any scenario, but rather a tool.”

Kiron was launched after Zimmer and Kressler realized that high fees, bureaucracy, and a lack of knowledge were considerable obstacles for refugees hoping to study at universities. Failing to meet higher application requirements due to lost passports, missing documentation, and the absence of former education certificates was all too common. The result was long administrative delays, during which refugees were unable to study and begin the process of rebuilding their lives through education.

“The only thing they prove to us is that they are refugees, and then studying with Kiron is completely free of charge,” said Laura Marwede, chief partnerships officer at Kiron. “We offer five different study tracks and a preparatory program, language courses for German and English, and support services, such as a corporate mentoring in Germany.”

Overall, Kiron partners with 56 universities. By providing access to MOOCs (massive open online courses)—which include courses produced by universities such as Harvard and Yale—Kiron’s refugee students can study flexibly online from anywhere.

Kiron’s courses meet the standards of the European Higher Education Area and allow students to start studying without further delay. The flexible approach means some students just take a few courses before getting into university, while others can study for longer periods until they fulfill the criteria to apply to university and transfer to an off line study program.

According to Marwede, the latest figures from UNCHR, the UN Refugee Agency, show that only 1 percent of all refugees worldwide have access to education. “When you think about how education is totally intertwined with integration, I think it’s so obvious that higher education is essential, which is why we identified this gap,” she said. “It’s about enabling refugees to redefine who they are.” Marwede said one of their customers recently said that for two years, she’d been feeling like a refugee, and now for the first time she felt like a student.

In 2014, while the Syrian civil war raged and ISIS took over Mosul in Iraq, Alexandra Clare spotted another widening educational gap for Syrian refugees and internally displaced Iraqis. Humanitarian organizations were training people as mechanics and cooks, but young people with degrees and those forced to quit studying were being overlooked. “More importantly,” said Clare, “no humanitarian organization was preparing conflict-affected youth for the future of work, which is inevitably intertwined with technology.”

In response, she launched nonprofit coding boot camp Re:Coded with Marcello Bonatto; they were inspired by emerging boot camps in the U.S., which could “quickly up-skill people with in-demand coding knowledge.” Since then, they have trained more than 300 students aged 17–30 on the 19-week program. The course comprises three stages: intensive coding, soft skills training, and a final client project. Students are taught by experienced developers using online educational resources Udacity and Flatiron School to teach the students using a blended learning approach.

However, coding knowledge is just one aspect of the program’s overall impact. “At Re:Coded, we care deeply about our students and follow their lives and progress every step of the way,” said Clare. “They not only gain new marketable skills quickly, but also change attitudes and behaviors, becoming more confident in their capacity to follow dreams and change the reality around them.”

The team are now looking to secure long-term funding so they can look beyond operating on a program-to-program basis. “Our goal is to receive $3 million to fund three years of operations across Iraq and Turkey,” she said, “including our coding boot camps, freelancing academy, a potential accelerator in Iraq, and women-only coding clubs and programs.”

As Techfugees’ Goube says, technology is no silver bullet in any scenario, but rather a tool that requires human interaction and implementation. That’s why a motivated global community of tech stakeholders focused on solving refugees’ problems has the potential to be so powerful. “Technology has unlocked immense potential around the globe,” she said. “We believe that we have barely scratched the surface in terms of how technology can revolutionize humanitarian aid and scale social impact.”